“Deadliest tornado season ever.” “Most aggressive hurricane season forecast ever.” “Hottest year on record.” “Early wildfires in California could signal worse to come.” Volcanoes are erupting, glaciers are melting, and cities are flooding around the world. These are all signs that the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) prediction is true.

As AccuWeather reports, last week, the WMO warned that the likelihood Earth’s average temperature will temporarily surpass 1.5 degrees Celsius in the next five years has risen to 80%. That 80% chance of at least one of the next five years through 2028 exceeding the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit established in the Paris Climate Agreement “has risen steadily” since it was signed 2015 , “when such a chance was close to zero,” according to the WMO.

The chance was 20% from 2017-2021 and more than tripled to 66% for 2023-2027. “We are playing Russian roulette with our planet,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said Wednesday.

The WMO warned last year in May that global temperatures are likely to soar to historic levels over the next five years due to increased greenhouse gases that would give rise to extreme weather events. It now said at least one year between 2024 and 2028 will beat 2023 as the warmest on record.

“We need an exit ramp off the highway to climate hell,” Guterres said in his remarks, adding how “the good news” is “we have control of the wheel” and the battle to limit Earth’s rise of temperature “will be won or lost in the 2020s — under the watch of leaders today.”

The WMO said this new report highlights the need and urgency of climate action. However, a WMO official pointed out that a short-term, or annual, warming does not equate to a “permanent breach” of the lower 1.5 degrees Celsius under the Paris Agreement’s goal.

The Paris Climate Agreement, which the Trump administration in 2019 gave notice of the United States’ intent to withdraw from, aims to limit those increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius. President Joe Biden re-entered the agreement in 2021 on his first day in office.

The world’s average temperature on land and the oceans’ surface set a global record in 2023, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration likewise confirmed in January this year.

Under the Paris Agreement, 196 countries agreed to keep the long-term global average surface temperature well below the 2 degrees Celsius mark above pre-industrial levels at the turn of the 20th century and committed to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of this century.

“Behind these statistics lies the bleak reality that we are way off track to meet the goals set in the Paris Agreement,” WMO’s Deputy Secretary-General Ko Barrett said.

The U.N.’s 2023 Emissions Gap Report found that greenhouse gas emissions are projected to increase by 3% in 2030, which is an improvement from the 16% increase projected at the time the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015. But emissions remain, for now, above levels needed to meet goals for limiting global temperature increases.

“We must urgently do more to cut greenhouse gas emissions, or we will pay an increasingly heavy price in terms of trillions of dollars in economic costs, millions of lives affected by more extreme weather and extensive damage to the environment and biodiversity,” Barrett said.

The scientific community has repeatedly warned that warming of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius risks unleashing “far more severe climate change impacts and extreme weather and every fraction of a degree of warming matters,” the WMO said.

The WMO report arrived the same day the U.N. Secretary-General gave remarks at New York’s American Museum of Natural History where he was blunt about the news on World Environment Day, which he called “the hottest May in recorded history.”

“Our planet is trying to tell us something, but we don’t seem to be listening,” he said as he noted the museum’s location and its significance to history.

“We’re not only in danger, we are the danger,” he said. “But we are also the solution.”

“The truth is, global emissions need to fall 9% every year until 2030 to keep the 1.5 degree limit alive,” Guterre said Wednesday as he noted the world is “heading in the wrong direction.”

WMO predicts further reductions in sea-ice concentration through the next five years in the Barents Sea above Norway and Russia, the Bering Sea in the northern Pacific Ocean and Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific above Japan to Russia’s far east. Guterres on Wednesday called the 1.5 degree threshold “not a target, it’s not a goal, it’s a physical limit” as he spoke of the possible collapse of Greenland’s ice sheet.

A study released last year led by James Hansen, a scientist responsible for raising public consciousness about climate change in the 1980s, suggested global temperatures were increasing faster than expected. It said that global temperatures will reach a crucial 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the year 2050, which is faster than what was previously expected by scientific consensus.

Climate scientists figured that July 4 last year was the hottest-ever day on record for average global temperature, followed months later with the news that November 2022 through October 2023 was the hottest period since records began in 1850, impacting 90% of Earth’s population. “We are living in unprecedented times,” said Carlo Buontempo, Director of Copernicus Climate Change Service. “But we also have unprecedented skill in monitoring the climate and this can help inform our actions.”

Last year’s high temperatures were blamed on “exceptional anomalies,” boosted by a strong El Nino, which supposedly pushed Earth’s mean temperature substantially above the pre-industrial average and 0.1 degrees Celsius higher than the last warmest year on record in 2016.

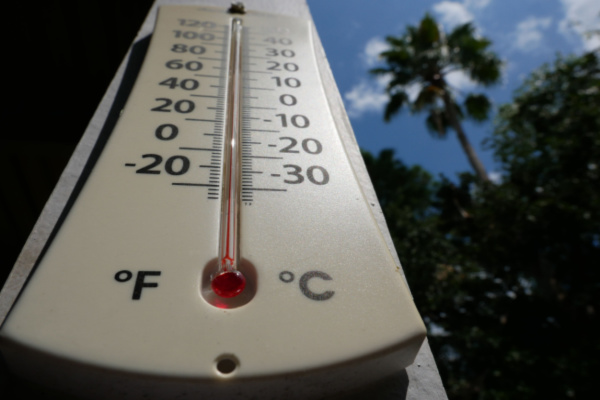

NOAA data show the average recorded temperature in 2023 was 58.96 degrees Fahrenheit, which is 2.12 degrees higher than the global average for the 20th century. The average global temperature reported for 2023 is 0.27 degrees more than the prior record high set in 2016.

A recent study showed that if global temperatures grow by 2 degrees Celsius, areas in Pakistan, India’s Indus River Valley, eastern China and sub-Saharan Africa will have many hours of heat exceeding what humans can stand every year, affecting about 4 billion people.

These areas are notably home to lower-to-middle income countries, where many people likely have little or no access to air conditioning during heat waves. “This string of hottest months will be remembered as comparatively cold but if we manage to stabilize the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere in the very near future,” Buontempo said, “we might be able to return to these ‘cold’ temperatures by the end of the century.”

—

Photo Credit: Collective Arcana / Shutterstock.com