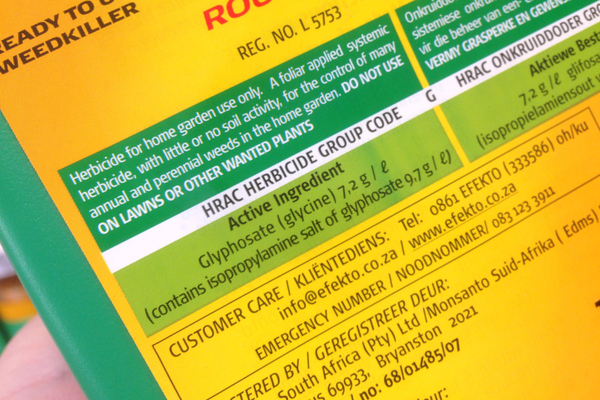

It’s in breakfast cereals, gardens and garages, and it could be deadly. Glyphosate, a chemical that kills weeds, is the most widely used herbicide in the country. It is in over 750 products sold in the U.S., according to Oregon State University’s National Pesticide Information Center. While the chemical has been around for decades, people only recently realized it was making its way from farms to the dinner table.

Monsanto began selling Roundup – the main active ingredient of which is glyphosate – in 1974. More than 20 years later, the company developed genetically modified crops that could withstand direct exposure to the chemical. Farmers bought into the idea and started spraying more Roundup. And nearly 20 years after that, in 2015, the World Health Organization’s cancer agency dealt Monsanto a crippling blow. It determined that glyphosate is “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

Melissa Perry, a public health professor at George Washington University, says that for decades, “We’ve perceived glyphosate to be low toxicity and low risk,” and now we’re scrambling to catch up. To start, very little is known about how much of the pesticide is in peoples’ bodies or diets. Humans can be exposed to glyphosate through food, drinking water and working in the agriculture industry, among other things. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regularly tests Americans to gauge their exposure more than 300 chemicals – but not glyphosate. Including glyphosate in the group of chemicals we evaluate in the human body “is very much a public health necessity,” Perry says.

The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit activist group, recently petitioned the CDC to include the chemical in its National Biomonitoring Program, as exposure to glyphosate has jumped “dramatically” as its use has increased over the past two decades.

Food and water are also not regularly tested for glyphosate, but because the chemical is used as a weed killer, including weeds in fields and near water supplies, a recent analysis by the Environmental Working Group found it in 21 cereal and snack products. The two cereals with the highest levels of glyphosate were Cheerios, and Honey Nut Cheerios Medley Crunch, the analysis found. They contained between four and six times the group’s recommended health level for children.

The typical consumer should be paying attention to these developments, according to Perry. “If I were an average member of the general population, I would say ‘I don’t know if I’m happy about having pesticides in my food,'” Perry says. In 2017, California added glyphosate to the list of substances under Proposition 65, its right-to-know law that warns residents about cancer-causing chemicals. Roundup producer Monsanto is challenging the rule in federal court, and a judge has put a temporary hold on the state’s cancer warning label requirement for products containing glyphosate.

The Environmental Protection Agency this month responded to California’s decision with pushback. It announced it will not approve such labels for products containing glyphosate, saying it would “constitute a false and misleading statement.” California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment called the EPA’s decision a mischaracterization of the law, adding that it is “disrespectful of the scientific process.” The move comes after the agency in April reaffirmed its conclusion that glyphosate does not cause cancer. The EPA’s findings are “consistent with the conclusions of science reviews by many other countries and other federal agencies,” it said in a press release.

Lawyers for Bayer AG, the parent company of Monsanto, have cited the agency’s determination in lawsuits from plaintiffs who say the weed killer contributed to their cancers. But the findings didn’t convince three consecutive juries that have sided with the plaintiffs, who were awarded billions of dollars in damages. Judges have reduced the amounts, which Bayer called a step in the right direction. It will be a long time before the plaintiffs see that money – if they ever do – because Bayer continues to appeal all three verdicts. The company argued that most cases of the plaintiffs’ type of cancer – non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – do not have known causes and that there isn’t enough scientific evidence to link Roundup to their cancers.

Lianne Sheppard, a professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington, previously stated in an interview with U.S. News that she disagrees with EPA’s recent conclusions and thinks the jury verdicts have been consistent with scientific findings on glyphosate. Sheppard previously served on the EPA’s scientific advisory panel to examine the carcinogenic potential of glyphosate. After leaving the group, she found in her own research that glyphosate exposure increases a person’s cancer risk by 41%. Bayer has pushed back against the study, saying it was “statistical manipulation.”

These first few cases are telling and important for Bayer’s future, as thousands of similar cases are pending at the federal and state level, and several jurisdictions, including Los Angeles County, have taken action into their own hands through bans on glyphosate use.

—

Photo Credit: A. Mertens / Shutterstock.com