Face blindness had been previously estimated to affect between 2 and 2.5 percent of people in the world. But in a study published last year by researchers at Harvard Medical School and the VA Boston Healthcare System is providing fresh insights into the disorder, suggesting it may be more common than currently believed.

In the new study, led by Joseph DeGutis, HMS associate professor of psychiatry at VA Boston, the researchers found that face blindness lies on a spectrum — one that can range in severity and presentation — rather than representing a discrete group.

Published in February 2023 in Cortex, the study findings indicate that as many as one in 33 people (3.08 percent) may meet the criteria for face blindness, or prosopagnosia. This translates to more than 10 million Americans, the research team said. The study found similar face-matching performance between people diagnosed with prosopagnosia using stricter vs. looser criteria, suggesting that diagnostic criteria should be expanded to be more inclusive. That could lead to new diagnoses among millions who may have the disorder but don’t realize it.

The take-home message is that prosopagnosia lies on a continuum and stricter vs. looser diagnostic criteria employed in prosopagnosia studies in the past 13 years have identified mechanistically very similar populations, providing justification for expanding the criteria to include those with milder forms of it.

At least one in 50 people have prosopagnosia, which steals the ability to recognize or remember faces. Sacks himself suffered with the condition before his death in 2015.

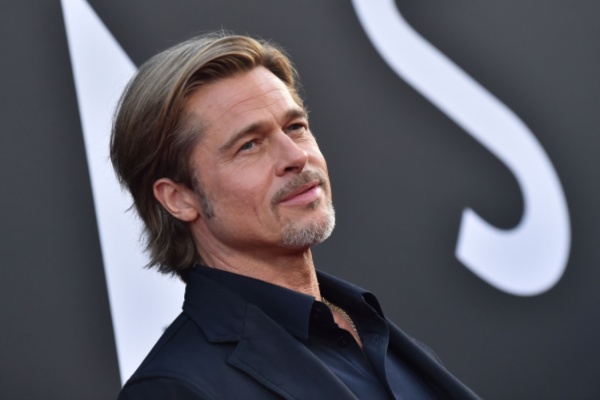

Other noted people with the disorder include legendary primatologist Jane Goodall, actor Brad Pitt, and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. Locally, U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper has managed a successful political career despite trouble recognizing faces.

What is Face Blindness?

Face blindness, also known as prosopagnosia, refers to a neurological disorder characterized by the inability to recognize familiar faces. When looking at a face, people with face blindness understand that they are viewing a face; however, they cannot identify individuals. Individuals with face blindness may have trouble identifying a family member or themselves. There are two types of impaired facial recognition: developmental, which is estimated to occur in as many as 1 in every 50 people, and acquired, which is quite rare.

Individual experiences of face blindness can vary. On the one hand, some people with face blindness cannot identify facial characteristics – they see only a blurred image of someone’s face. This is called defective face processing, or apperceptive prosopagnosia. Others who have face blindness identify facial features with clarity, but they cannot associate the faces they see with familiar individuals, like friends, relatives, or famous people. This variety is known as associative prosopagnosia.

Facial blindness severity varies among patients, ranging from having trouble identifying only periodic acquaintances to being unable to recognize spouses or even their own faces.

What causes face blindness?

The causes of face blindness differ depending on the type of face blindness. Developmental face blindness is a congenital disorder, in which individuals are born with an inability to develop face recognition skills despite having unimpaired vision and memory. While there is no presence of obvious brain lesions, several studies have revealed that these individuals may have anatomical differences in regions of the brain associated with face processing, like the fusiform gyrus area in the basal surface of the temporal and occipital lobe.

Developmental face blindness may have a genetic basis, as it commonly runs in families and can be present in multiple family members. However, the exact genes that control facial recognition have not yet been identified. Notably, monozygotic twins (i.e., identical twins) have similar face recognition skills, whereas dizygotic twins (i.e., fraternal twins), demonstrate different facial recognition abilities. Interestingly, developmental prosopagnosia appears to present more frequently in individuals with autism spectrum disorder, even though these conditions are independent of one another.

Acquired face blindness, however, often results from severe brain injury to the temporal lobe, particularly the fusiform gyrus. Various types of brain injury — including head trauma, inadequate blood supply to the brain (i.e. a stroke), and inflammation of the brain (i.e. encephalitis) — can suddenly cause problems with facial recognition. In addition, acquired face blindness can result from brain lesions, such as tumors. Finally, brain degenerating diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, can also cause acquired face blindness, as they gradually reduce the size and abilities of parts of the brain.

What are the Signs and Symptoms?

Prosopagnosia is thought to affect many aspects of life. In addition to being unable to recognize faces, individuals with face blindness may have trouble identifying facial expressions of emotion, like anger, surprise, or joy. For those who have face blindness, getting to know new people and forming relationships can be extremely difficult, and social struggles may lead to feeling isolated, lonely, or depressed. It is very common for individuals with face blindness to avoid social interaction and develop severe social anxiety, an overwhelming fear of interacting in social situations.

Moreover, face blindness also makes it challenging to keep track of each of the different characters in movies or television shows, so affected individuals may have trouble staying engaged, whether they are watching for their own entertainment or as a way to spend time with others.

Finally, people with face blindness often lose their ability to recognize objects or places they have visited before, so navigation can be a struggle as well.

How is face blindness diagnosed and treated?

While no “cure” exists for facial blindness, people experiencing problems should seek care, as behavioral and physical therapies can help with adapting to the condition. Experts suspect case numbers might be underreported due to lack of awareness. “Sometimes people don’t recognize they have it,” Filley said. “Or they might just accept it, thinking that ‘I’m just weird or eccentric,’ when it actually turns out they have a neurological problem.”

Diagnosis typically begins with an assessment of the individual’s history and a thorough physical examination. The examination typically involves a range of tests, such as the Cambridge Face Memory Test (CFMT). Individuals may be asked to memorize and later identify the faces of people they have never seen before. They may also be asked to identify famous characters, find similarities and differences between given faces, or estimate someone’s age and facial expression.. In cases of acquired prosopagnosia, further diagnostic testing may be needed in order to identify the underlying cause. Blood tests can evaluate the presence of inflammation, and imaging, such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can reveal brain damage.

Intensive programs, published for rehabilitation specialists to follow, allow people to compensate for the condition, Pelak said. One thing that the brain can do, depending on the cause of facial blindness, is use other non-facial features to recognize that person, including gait, voice, mannerisms, hair styles, facial hair, etc., she said.

With acquired facial blindness, treating the underlying cause early can potentially change the course for patients, such as clot-busting drugs for strokes (which must be given within 4.5 hours of onset) or newly approved Alzheimer’s drugs that can slow brain degeneration, Pelak said.

Advances in facial recognition technology could eventually offer solutions for some patients, Pelak said. “There is already technology in the low-vision world where you aim the technology at something and it tells you what you’re seeing,” she said. “That obviously involves a high level of interaction with the person who’s using the technology,” so it would not work for someone with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease, for instance, she said. “But there is a lot of hope on the horizon.”

—

Photo Credit: DFree / Shutterstock.com