A growing El Niño in the Pacific Ocean would normally foreshadow a slower-than-normal Atlantic hurricane season. This year, however, may be different.

As The Weather Network reports, temperatures across the Atlantic Ocean are running much higher than normal, to the point that experts are astounded by the temperature anomalies we’ve seen in the past couple of months.

This unusual warmth in the Atlantic may overpower El Niño’s influence just enough to allow this hurricane season to churn out more than a dozen named storms, according to a new forecast released by experts with Colorado State University (CSU).

CSU’s latest forecast on July 6 called for 18 named tropical storms across the Atlantic basin this year, which is up from previous predictions of 15 storms (June 1) and 13 storms (April 13).

A typical season would see 14 named storms, seven of which grow into hurricanes, and three of those hurricanes achieving ‘major’ status with winds of Category 3 or stronger on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

The initial predictions of a near- or below-normal hurricane season stemmed from a growing El Niño in the eastern Pacific Ocean, a pattern of warmer water off western South America that affects global weather patterns.

One such effect is an uptick in wind shear that blows east over the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic. Wind shear is destructive to any tropical system trying to organize and strengthen, so we typically see slower-than-normal hurricane seasons when El Niño conditions are present.

While we’re rapidly diving into an El Niño that looks like it could grow quite strong in the months ahead, the true wild card as we approach the peak of hurricane season is the widespread, record-breaking warmth found throughout the Atlantic basin.

Sea surface temperature anomalies across the Atlantic are “unprecedented,” as climate experts with the World Meteorological Organization noted in a recent blog post. The Atlantic Ocean’s fever is likely due to a combination of recent weather patterns and “longer-term changes in the ocean,” the agency said.

It’s a bit of a balancing act trying to figure out whether El Niño or raging Atlantic warmth will win out as the peak of hurricane season nears in August and September, which is why the CSU forecast emphasizes lower-than-usual confidence.

But it would only take a relatively small window of favourable ingredients coming together to allow a storm to develop and thrive when the ocean is this unusually warm. This year’s Atlantic hurricane season has racked up four ‘named’ storms through the beginning of July.

Calling the first storm ‘named’ is a bit of a quirk this year. The season’s first storm formed back in January south of Nova Scotia. That storm actually didn’t receive a name at the time — the U.S. National Hurricane Center opted to classify it in a post-analysis in May, setting its fate to live forever in the records as “Unnamed Subtropical Storm.”

The other three systems — Arlene, Bret, and Cindy — all formed in the first three weeks of June. “As is the case with all hurricane seasons,” the CSU team noted in their release, “coastal residents are reminded that it only takes one hurricane making landfall to make it an active season for them.”

Plenty of seasons that saw below-normal activity wound up producing historic and tragic hurricanes. El Niño played a role in the incredibly slow start to the 1992 Atlantic hurricane season, which didn’t see its first named storm until late August. That storm was Hurricane Andrew, a scale-topping storm that unleashed catastrophic damage across southern Florida.

—

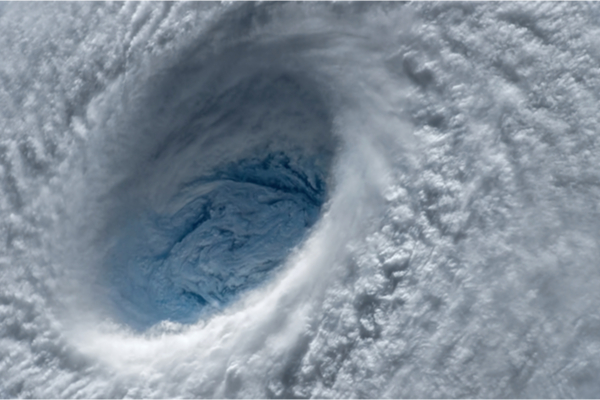

Photo Credit: Evgeniyqw / Shutterstock.com